What Happens to the Hands and How Can Surgery Help?

In cerebral palsy, part of the brain that controls movement in the arms can be affected. The severity is variable. Some patients have very mild effects whilst others develop severe difficulties from the beginning. Cerebral palsy is the biggest group of patients that I treat, but there are many other causes of damage to this key part of the brain such as head injury, infection, tumour, strokes and a range of rarer medical conditions – patients with any of these can be seen in my clinic.

The Hardware

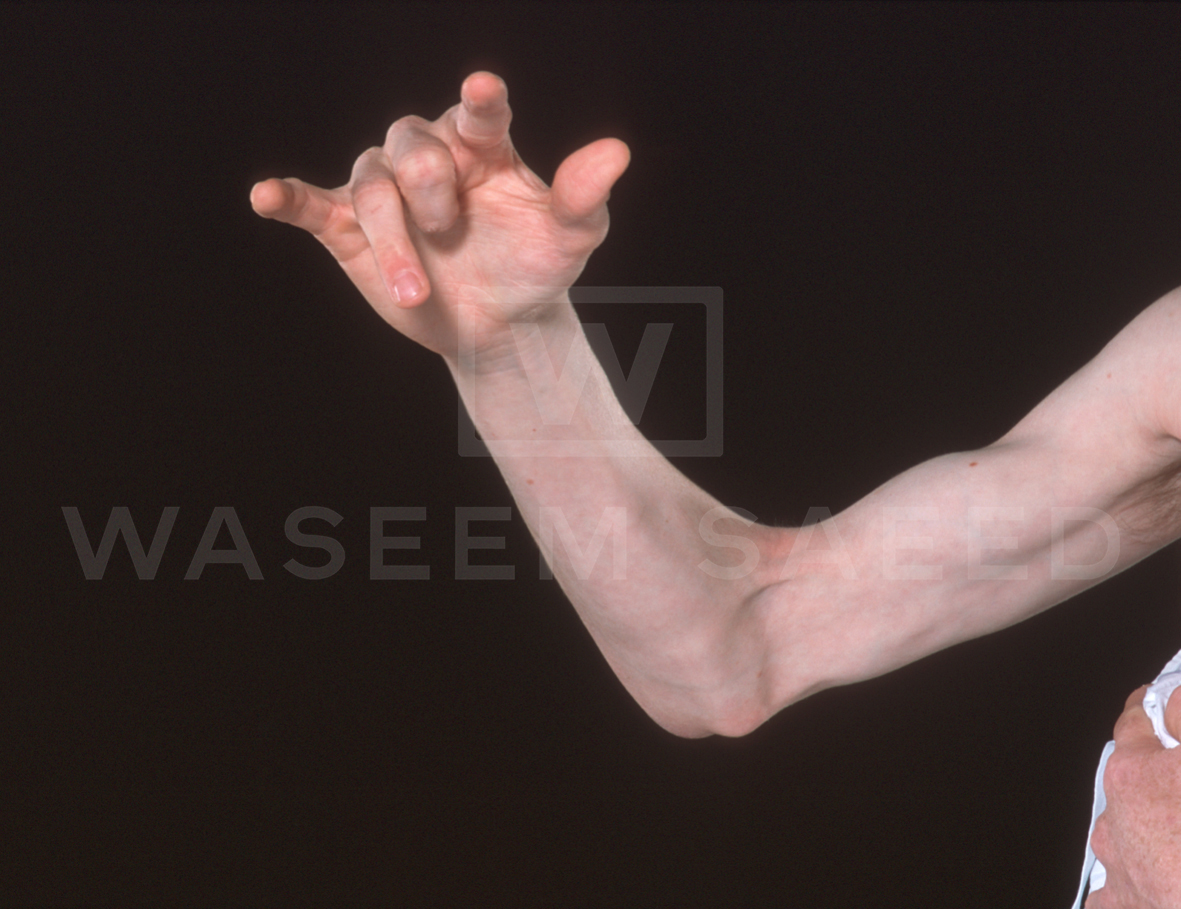

The key principle is that in the vast majority of patients the muscles, joints and soft-tissues of the hand and arm (what I call ‘hardware’) are in good condition when the child is born. The signals from the brain to the limb however are disorganised. This means that some muscles do not contract (weakness); others contract too strongly (spasticity). There is disorganisation of the sense of what the limb is doing (loss of position sense and coordination), combined with an impairment of feeling (reduced sensation). In other words the brain (what I call the ‘software’) is not controlling the limb adequately.

As a result the joints get out of balance and muscles stretch and weaken further. Other muscles get so tight they cannot be stretched. Joints stiffen in unhelpful positions. Those affected try to overcome these difficulties by adapting their movements – ironically these adaptations can worsen the tightness. A vicious cycle of disability and lack of use can follow.

With surgery my aim is to restore the ‘hardware’ – re-balance the muscles and joints. This is intended to break the cycle. You should understand that I cannot improve the ‘software’ – that needs exercise and practice. It is important also to realise that in some patients surgery is not required or is unlikely to be helpful.

The Software

Surgery can re-balance muscles and joints, but ultimately that alone will only give limited or short-lived improvement – the key is improving the ‘software’ or in other words learning to use the limb after surgery. This has been the most gratifying part of operating on my patients and is particularly the case with children. Contrary to traditional views many of my patients of all ages have shown me that they can learn to use their hands to varying degrees if I can give them something to work with. Furthermore I do not believe that we lose this ability with age – how else could an adult learn to play a musical instrument from scratch?

It does however require commitment to exercises after surgery, often for many months. This is an integral aspect of the treatment and guided by myself and our senior physio and occupational therapists.